Where to mark Remembrance Day 2024 in Metro Vancouver. CTV News:

Preparations are underway across Metro Vancouver for Remembrance Day ceremonies large and small in honour of Canadian soldiers who made the ultimate sacrifice for their country.

Vancouver's largest Remembrance Day gathering is also the oldest annual ceremony in the city. This year marks the 100th annual ceremony at the cenotaph in Victory Square on West Hastings Street. The first was held in 1924.

This year's event begins at 10 a.m., and more than 15,000 people are expected to attend. The event program is published on the city's website.

The Vancouver Police Pipe Band will perform at a Remembrance Day service at the cenotaph in Vancouver's Memorial South Park, on 41st east of Fraser. The ceremony begins at 10:40 a.m.

The balance of power

The most important divide in international politics isn't between good and evil. It's between those powers which seek to support the status quo, and those which seek to overturn it. Canada depends on stability and trade: we're a status quo power. Today, the countries supporting the status quo are the US and its allies. Those opposed to the status quo are China, Russia, and Iran.

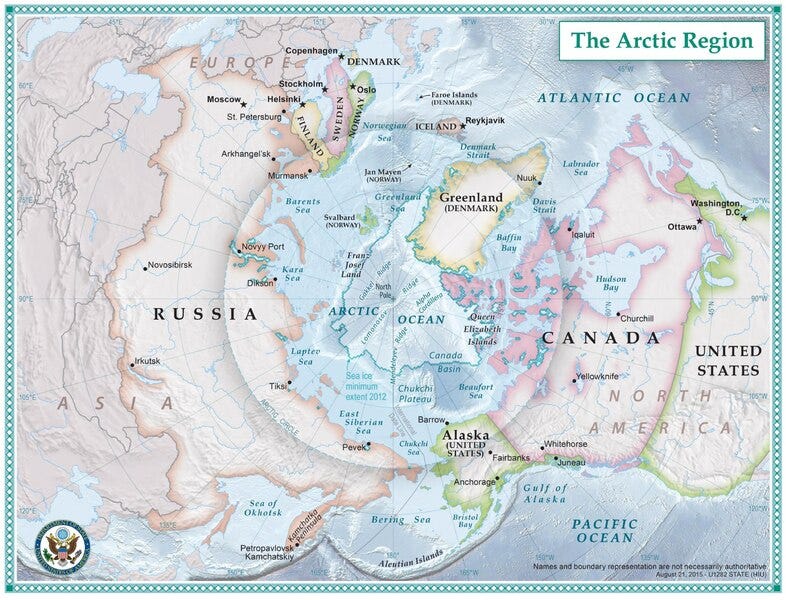

Canada's basic security challenge is similar to that of Britain: maintain the balance of power in Europe and Asia, so that no single power dominates the rest, putting it in a position to expand overseas. That's why Canada's a NATO member, and why Canada fought in World War I and II: to prevent Germany (under Wilhelm II and then Hitler) and then the Soviet Union from conquering Europe.

We're not going to fight anyone single-handedly, which is why our alliances (especially NATO) are so important.

Churchill, 1936:

For four hundred years the foreign policy of England has been to oppose the strongest, most aggressive, most dominating Power on the Continent, and particularly to prevent the Low Countries falling into the hands of such a Power. Viewed in the light of history these four centuries of consistent purpose amid so many changes of names and facts, of circumstances and conditions, must rank as one of the most remarkable episodes which the records of any race, nation, state or people can show. Moreover, on all occasions England took the more difficult course.

Faced by Philip II of Spain, against Louis XIV under William III and Marlborough, against Napoleon, against William II of Germany, it would have been easy and must have been very tempting to join with the stronger and share the fruits of his conquest. However, we always took the harder course, joined with the less strong Powers, made a combination among them, and thus defeated and frustrated the Continental military tyrant whoever he was, whatever nation he led.

Thus we preserved the liberties of Europe, protected the growth of its vivacious and varied society, and emerged after four terrible struggles with an ever-growing fame and widening Empire, and with the Low Countries safely protected in their independence. Here is the wonderful unconscious tradition of British foreign policy.

I know of nothing that has happened to human nature which in the slightest degree alters the validity of their conclusions. I know of nothing in military, political, economic, or scientific fact which makes me feel that we are less capable. I know of nothing which makes me feel that we might not, or cannot, march along the same road. I venture to put this very general proposition before you because it seems to me that if it is accepted everything else becomes much more simple.

Observe that the policy of England takes no account of which nation it is that seeks the overlordship of Europe. The question is not whether it is Spain, or the French Monarchy, or the French Empire, or the German Empire, or the Hitler regime. It has nothing to do with rulers or nations; it is concerned solely with whoever is the strongest or the potentially dominating tyrant. Therefore we should not be afraid of being accused of being pro-French or anti-German. If the circumstances were reversed, we could equally be pro-German and anti-French. It is a law of public policy which we are following, and not a mere expedient dictated by accidental circumstances, or likes and dislikes, or any other sentiment.

George F. Kennan, 1950:

Today, standing at the end rather than the beginning of this half-century, some of us see certain fundamental elements on which we suspect that American security has rested. We can see that our security has been dependent throughout much of our history on the position of Britain; that Canada, in particular, has been a useful and indispensable hostage to good relations between our country and British Empire; and that Britain's position, in turn, has depended on the maintenance of a balance of power on the European Continent.

Thus it was essential to us, as it was to Britain, that no single Continental land power should come to dominate the entire Eurasian land mass. Our interest has lain rather in the maintenance of some sort of stable balance among the powers of the interior, in order that none of them should effect the subjugation of the others, conquer the seafaring fringes of the land mass, become a great sea power as well as land power, shatter the position of England, and enter - as in these circumstances it certainly would - on an overseas expansion hostile to ourselves and supported by the immense resources of the interior of Europe and Asia.

Canada’s war dead

Hundreds of thousands of Canadians fought in World War I and World War II; tens of thousands died. C. P. Stacey, Canada in the Age of Conflict, Volume 1, 1977:

[Stephen Leacock's "Sunshine Sketches of a Little Town," published in 1912] is no bad symbol of Canada as it was just before the people of the land of hope found themselves, unbelievably, deeply engaged in a world war. It is a simple and isolated place, unutterably remote from the quarrels of the chancelleries of Europe which are so soon to plunge Canadians into death, mutilation, private misery, and political disruption. Its people work hard to earn modest livings. A less military community can scarcely be imagined. ... By European standards Canada was still what she had been in 1867, a country utterly without military power. It is extraordinary to think that by 1915 the men from Mariposa were crossing bayonets with the Prussian Guard.

We tend to think of World War II and the Cold War as completely separate, when in fact the Cold War reflected the lack of a settlement after World War II. Hannah Arendt, writing in 1951, described World War I, World War II, and the Cold War as one continuous crisis:

Two World Wars in one generation, separated by an uninterrupted chain of local wars and revolutions, followed by no peace treaty for the vanquished and no respite for the victor, have ended in the anticipation of a third World War between the two remaining world powers. This moment of anticipation is like the calm that settles after all hopes have died.

During the Cold War, Canadian soldiers were stationed in Western Europe as part of NATO’s defenses against the Soviet Union, and fought in the Korean War against North Korea and China.

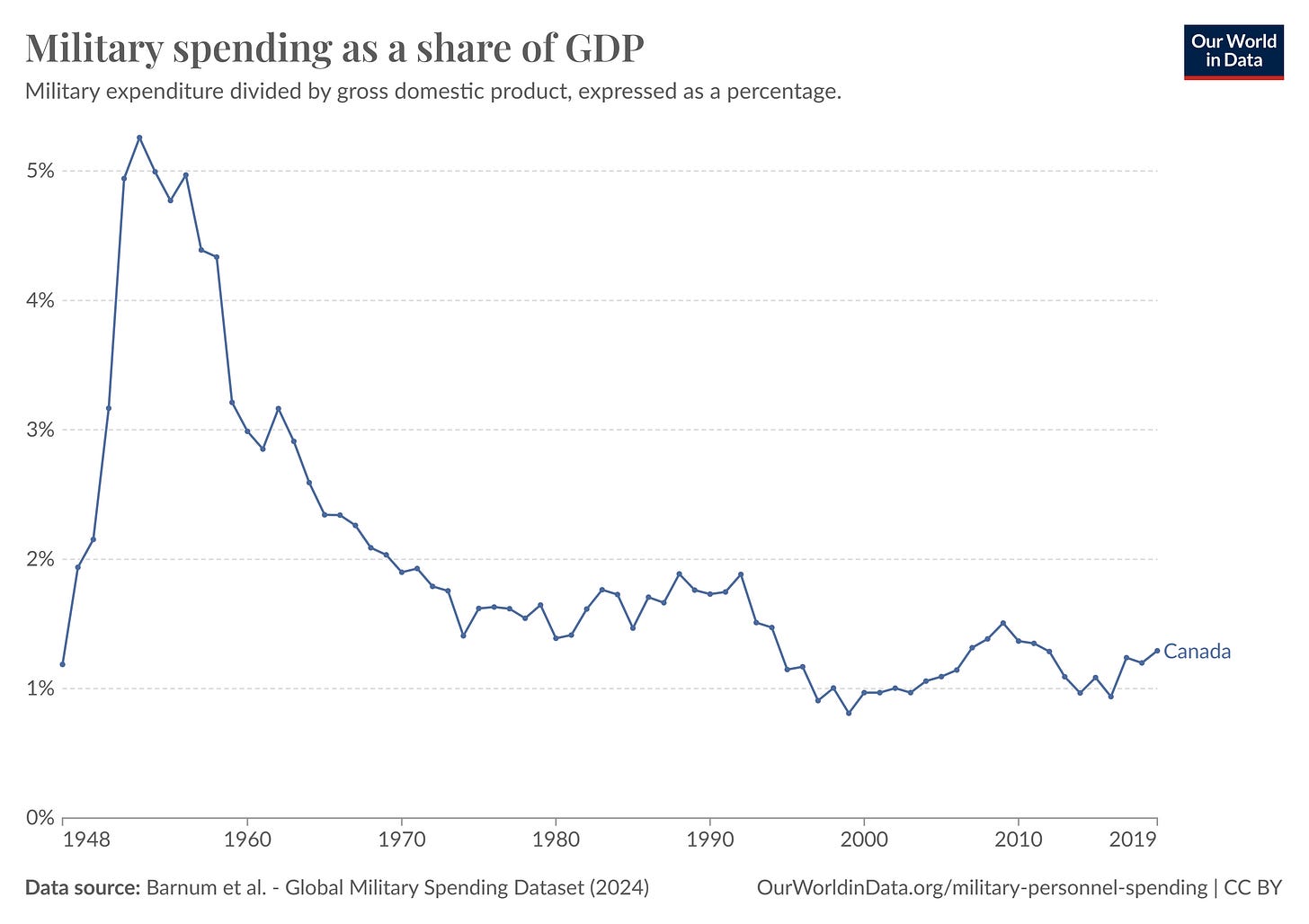

After the Cold War ended in 1989, Canadian military spending fell precipitously, but Canadian soldiers fought in the Gulf War against Iraq, Canadian peacekeepers served in the former Yugoslavia (fighting in the Battle of Medak Pocket), and after al-Qaeda’s attack against the US in 2001, Canadian soldiers fought in Afghanistan against al-Qaeda and the Taliban.

Trouble ahead

Since the end of World War II, we’ve been accustomed to taking our security for granted, given that we're next door to the US. We think of ourselves as far from the front lines. The military budget has been an easy target for spending cuts. It’s going to be difficult to persuade the Canadian public that we need to be prepared for war, compared to a country which is closer to the front lines and more directly threatened (like Germany, South Korea, or Australia). I suspect we’ll need cross-party consensus - at least between the Liberals and Conservatives - to be able to increase military spending.

Because we’re next door to the US, Canada has a strong self-interest in multilateral alliances (e.g. NATO), so that we don't end up completely at the mercy of the US. Canada is facing increasing pressure from our European allies as well as the US to contribute more. Plus we're now in a more insecure and unpredictable world. It's not just Trump's election in 2016 and his re-election last week, and Russia launching a full-scale attack on Ukraine. China under Xi Jinping has adopted a much more aggressive, "might makes right" approach to diplomacy, and in this view, a small country like Canada can easily be bullied. As Stephanie Carvin puts it, we're living through the shitty version of the Melian Dialogue; we don't want to be treated like the runt of the litter.

Foreign policy requires matching our ends and our means. In a more dangerous and unpredictable world, we’re going to be spending a lot more on soldiers, spies, and diplomats, while getting less security as a result.

We have a tendency to take a rather moralistic approach to foreign policy. This is a long tradition: Dean Acheson described Canada as “the stern daughter of the voice of God” (this was not a compliment). I think we're going to have to adjust our attitude in a more pragmatic direction, with more limited goals.

Canada’s military needs

As a layperson, the most interesting discussion I've seen of Canada's military needs was from reservist and blogger Bruce Rolston, back in 2003. He suggests focusing on rapid, independent, sustainable infantry deployment. We're also committed to the F-35s in case of high-intensity conflict.

They lost me at the aircraft carrier - on the need to set priorities

Okay, that wasn't very productive - current capabilities of Canada's navy, air force, and army

So here's one model - focus on rapid, independent, sustainable deployment of ground troops, giving Canada maximum flexibility.

A model for foreign deployment flexibility - what equipment would be needed to support deploying a reinforced battalion from each of the three regionally based brigades (Alberta, Ontario, Quebec).

Some points:

I'm also assuming that any proven domestic needs, will, as they always have been through Canadian military history, be served just as ably by trained soldiers whose primary focus of training and procurement is actually overseas service. Canada is a huge country, and any capability we have to move our troops to trouble spots abroad positively improves our ability to move troops within the country as well. Likewise with anti-terrorism, or intelligence... the capabilities that make your special forces or NBC units useful in foreign settings can only improve your domestic response ability as well. It is backwards, therefore, to fully man the "homeland defence" apparatus, and use the leftovers for foreign commitments... our defence of North America is always going to be a forward, interventionist defence, that hopefully puts the majority of the battles in someone else's country.

If one looks back on the primary limiting factor in the last 15 years on Canadian military operations (and hence on foreign policy planners as well), it has been rapid, independent, sustainable deployability. It prevented us from even considering many missions where we could have done some good (Congo, Rwanda, reinforcing our own troops in Yugoslavia when it was still a UN mandate, the most recent Gulf War, etc., etc.) It has also prevented us from doing as much as we could or wanted to in the missions we did accept (Afghanistan, Gulf War 1, Kosovo, East Timor, etc., etc.) In all cases there was a will, but no way: it stands to reason that if the military of the future is to be any better than it is today, if that $3 billion in spending is going to make a difference, then it has to be with this as its focus.

Of course, the troops that are most often needed were to be ground troops. Not because you need "boots on the ground," necessarily, but because ground deployment is basically the only kind that is useful regardless of the level of allied support, and across the spectrum of operational intensity. High, middle or low, with allies or without, soldiers are still useful... combat air power and naval assets less so. A destroyer can't peacekeep. A CF-18 can't defend a no-fire zone. An infantry company can. Yes, other assets can be useful too, but they inevitably must be one piece in larger allied operations. Canada could someday have the best attack helicopters in the world (for instance); it arguably has the best armoured recce unit or the best disaster assistance teams in the world now, but those are capabilities that, if Canada doesn't also provide the foot soldiers, someone else has to for us. It's good to have a few nichey, specialized tasks your country is very very good at... but for flexibility's sake you always want to have that one capability that always comes in handy, for us or any other army, in any circumstance. And that's trained and well-equipped combat soldiers.

Military procurement

Military procurement is a huge challenge.

Philippe Lagassé describes the National Shipbuilding Strategy, which is a long-term program supported by both the Liberals and Conservatives. Time to worry about our warships, October 2023.

A one-hour PowerPoint presentation on Canadian military procurement by an Australian analyst who’s anonymous (he goes by the pseudonym Perun) but well-regarded. In short: our military budget is inadequate, not enough of it is allocated to equipment, and we end up spending way too much for what we get.